Midweek Movie: Unlawful Entry (1992)

Los Angeles dreams of being infinite but breeds claustrophobia

Welcome to Midweek Movie. Each week, I will jut down some notes on the films I’m watching as inspiration for my own movie The Big Pay Off— a running log of narrative, thematic and visual inspiration.

Let’s be honest: Los Angeles is ugly. Sure, there are picturesque neighborhoods of giant oak trees and haciendas, biodiverse parks, scenic hills, as well as some nice beaches. But overall, no one would honestly describe the sprawl, the freeways, the rundown urban desertscape as pleasing to the eye.

However, it is precisely this ugliness that, in my opinion, makes Los Angeles so cinematic. The topography, the unwieldy urbanity, the free-for-all architecture— it all looks amazing on film. There was a time when productions used this look to its full effect. Unlawful Entry (1992) is just such a film. Directed by Jonathan Kaplan and starring Ray Liotta, Kurt Russell and Madeleine Stowe, the film tells the story of LAPD Officer Pete Davis (Liotta) who attends the call to a married couple’s house (Russell and Stowe) where a burglar held a knife to the wife’s throat. After he helps the couple install a security system, Davis becomes increasingly obssessed with the wife which escalates into murderous violence.

The three central performances by Liotta, Russell and Stowe are all excellent, but in my opinion the main character of the film is Los Angeles itself. The film opens with quite an amazing areal shot that connects the lawless streets of underdeveloped downtown Los Angeles to the seeming quiet and security of the affluent suburban neighborhoods to the North. In between, Los Angeles’ sprawl teems with ominous life. As Mike Davis writes in City of Quartz, “Los Angeles is a city without boundaries [that] dreams of being infinite.” Kaplan visualizes just this to amazing effect.

The opening visual also sets up the central theme of the movie perfectly. Here we have an prosperous couple who have to repeatedly confront danger and crime of the big city. What brings the danger to their door? Geography, destiny, social ills, personal obssession. The couple cannot escape any of it, no matter how much they try to turn their house into a fortress, or how well thought out their security plans are because in a “city without boundaries”, treacherousness is always just a short freeway ride away.

In one central scene, Liotta’s Pete Davis meets with Russell’s Michael Carr at the top of Runyon Canyon at night. A million pinpricks of light extend in front of the two men. While they act out their personal drama perched on the hill, ten million Angelenos swarm around in the proximate distance. The choice of location here is perfect— the city’s iconic expanse seems at first awesome but then becomes claustrophobic as the scene progresses. The breadth and anonimity of the city offers no refuge to Michael. Danger is always right in front of him, no matter what he does. In the middle of the scene, a coyote calls. “They still work these hills”, Pete whispers. Michael, the domesticated suburban striver, is up against a primordial form of violence, whether the animal is human or not.

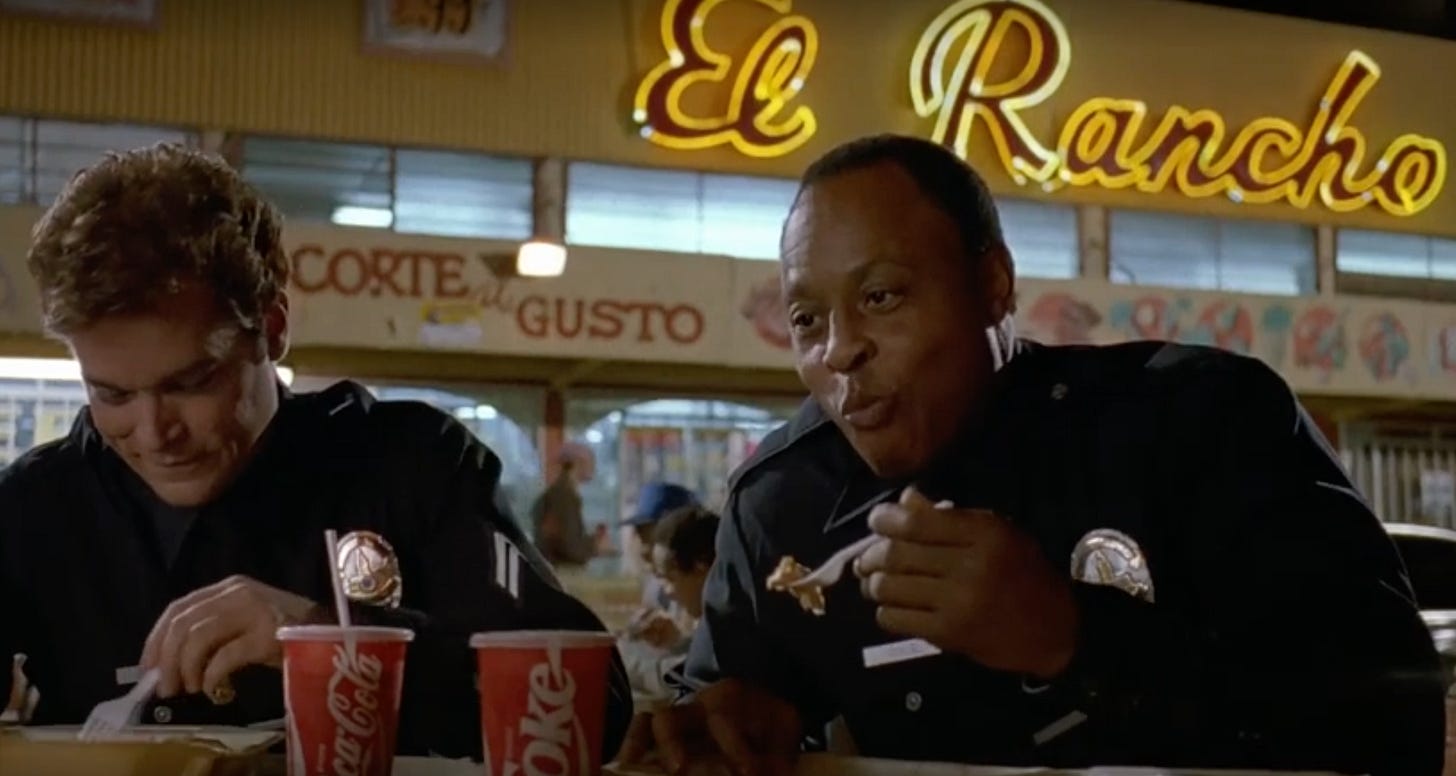

Earlier, Michael goes on a ridealong with Pete and his partner Roy (Roger Mosley). As they prowl through downtown’s rundown streets, the officers show Michael a version of Los Angeles he hasn’t known yet: a sort of second circle of hell where lustful women and criminals barely able to control their violent urges abound. When they get dinner at a Mexican restaurant in a mini-mall (located in Echo Park, a neighborhood used to great visual effect in The Shield as well), Pete quips, “if we were to search any one of these assholes, we’d be up to our butts in drugs and guns”. Michael doesn’t have the stomach for Mexican food nor this Dante’s Inferno version of Los Angeles.

It gets worse later on, when Pete takes Michael to a crack house next to a freeway exchange. The location is once again amazing: it visually juxtaposes the themes of urban decay encroaching on the glamour of palm trees and high rises in the distance. Pete offers Michael the opportunity to take revenge on the man who held a knife to his wife’s throat. But Michael can’t do it. He’s too civilized to engage in Pete’s world of primitive hierarchical violence. “I don’t want Pete around anymore”, Michael tells his wife Karen when he gets home that night. Kaplan makes it a point to show the red lights on the control panel of the couple’s security system signifying all entry points are secured. But of course we already know it can’t offer any real security against the nightmarish brutality lurking just outside the door.

I could go on and on about the use of locations in this film. Roy’s apartment in Hollywood, the Mayan theatre where Pete tries to open a night club, the back alleys in Westlake where Pete pursues and kills a drug dealer— Los Angeles plays itself in this movie, it shows off why it was once the movie capital of the world, it reminds us what we lose when we turn filmmaking into merely having actors stand on a green screen stage talking to a tennis ball. There is a grit, an immediacy, a thematic heft to this movie that is lacking in much of today’s “content” era of filmmaking. The characters exist in a real environment here, the movie has texture.

I strive to achieve this in The Big Pay Off as well. I want to locate characters in a recognizable environment that anchors and motivates their actions. I want to celebrate the ugliness of Los Angeles in all its beauty.